On the 5th Anniversary of the enforced disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students

Today marks the fifth anniversary of the 2014 enforced disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students and the killing of 6 people, students and bystanders, on the night of September 26th and early morning of the 27th in Iguala, Guerrero, in southwestern Mexico. The case of the 43 Ayotzinapa students has received widespread attention and stands for the ongoing internal conflict in Mexico, a conflict with global origins and in which Canada plays a prominent role.

Four months after the disappearance, Mexico’s previous administration (2012–2018) declared the case closed. The then-attorney general announced what he deemed the “historical truth”—that the 43 students were captured by municipal police forces and handed over to a local organized crime group that incinerated the students at a local dump. An interdisciplinary team of experts has refuted the federal government’s findings.

The current administration (2018–2024) has vowed to open an inquiry on the federal investigation of the Ayotzinapa case, including the actions of judges. To date, 53 of the 70 individuals arrested and charged with playing a role in the students’ disappearance have been released.

The 43 students remain missing and each year thousands of others join the growing list of reported missing persons cases. For every one missing Ayotzinapa student, there are around 930 people missing in Mexico.

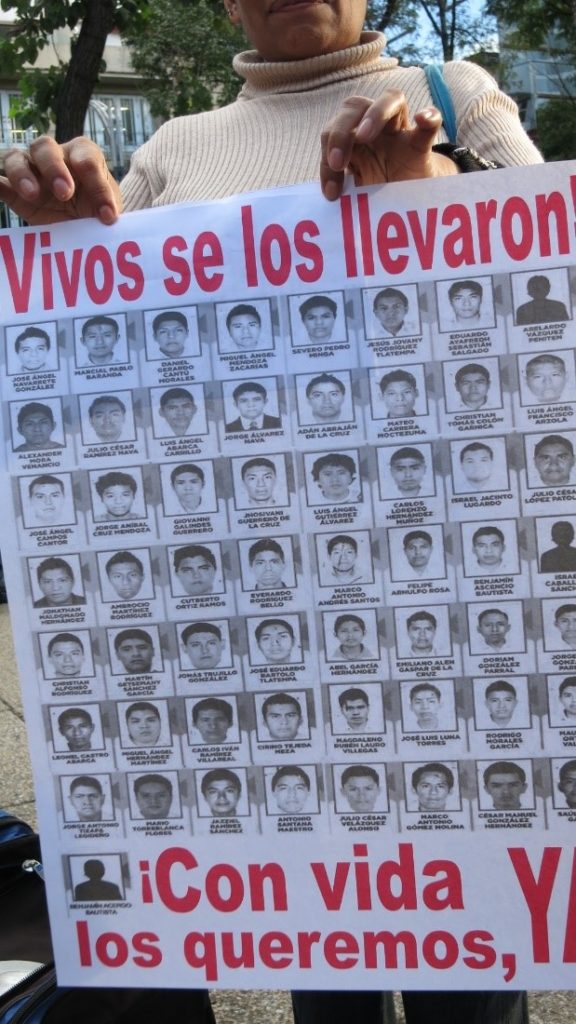

Woman holding a poster with the faces of the 43 Ayotzinapa students at a protest in Mexico City, October 2014. Photo Credit: Gabriela Jiménez

Since December 2006 when the then-president (2006–2012) mounted an attack on organized crime groups and drug trafficking, at least 40,000 people have disappeared. Mexico’s current federal government has revealed that in the last twelve years 5,000 bodies have been found in more than 3,000 clandestine graves across Mexico.

In 2015, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein, stated that between December 2006 and August 2015, 150,000 people were killed. Three years later, in 2018, The Wall Street Journal reported that Mexico’s “Drug War” had claimed 250,000 lives in twelve years.

Mexico’s feminicide rate is especially monstrous. According to INEGI (Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography), the feminicide rate quadrupled between 2007–2017; during this same time period, the number of women killed in public spaces surpassed those committed in the private realm. Moreover, the ways women and girls have been murdered and their bodies disposed of since 1993, when feminicides were first being reported on in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, anticipated and set the pattern for the gruesome ways people are murdered in Mexico today.

The criminalization, persecution, and targeted attacks of journalists and human rights defenders, particularly those protecting the environment amid large-scale extractive projects, is rampant. Annually, Mexico has seen a pattern of breaking the previous year’s record on the number of journalists and human rights defenders killed for their work.

To address security in Mexico, this year for the first time the federal government created the National Guard—further militarizing the country and its borders. Mexico’s National Guard has been deployed to Mexico’s southern border and popular migrant routes within the country’s territory to curtail migration to the United States as requested by that nation-state’s federal government.

The National Guard’s presence adds duress and extra obstacles for the predominantly Central American migrants and refugees who regularly encounter violence and the possibility of death on their journeys northward. Mexico’s president has also directed the National Guard to develop a national strategy to abate feminicides.

And let’s be clear: the violence Mexicans face is founded on international policies either agreed upon multilaterally or left unchallenged in the public sphere by nation-states (unwittingly) profiting from it. The internal conflict in Mexico has global roots, and Canada is implicated.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, Mexico, and the United States has facilitated the flow of commodities across borders. These flows accompany a global demand for and speculation on natural resources, of which Canada is a global leader. Extractive projects often lead to environmental degradation and contribute to climate change and social conflicts over territory, including the militarization of these areas through the presence of state and private security personnel.

Canada’s third safe country agreement with the United States prevents Central American migrants from requesting asylum here. Instead, migrants who reach the U.S. border are left to face the high probability of family separation and the violation of their human rights at private detention centers. It can be surmised that the United States serves as a thousands kilometers long border wall between Canada and the rest of the hemisphere, and therefore Canada is “benefitting” from the United States’ harsh immigration policies.

Canada’s federal election campaign season is well underway. Like the thousands of people searching for their missing loved ones and calling for justice across Mexico, Canadians must demand more of federal candidates and their immigration, foreign, and economic policy platforms, particularly those that have harmful impacts throughout Turtle Island.

The status quo is deadly.

By Gabriela Jiménez, Latin America Partnerships Coordinator